(An introductory page to the basics of mIRC and the mIRC Scripting Language) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Template:mIRC Guide}} | {{Template:mIRC Guide}} | ||

| − | This article focuses on the very basics of mIRC. The | + | This article focuses on the very basics of mIRC. The target audience is people with no knowledge, or very limited knowledge, of the [[mIRC scripting language]]. |

== Where does the code go? == | == Where does the code go? == | ||

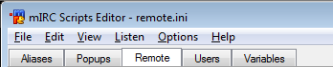

| − | All your code, regardless of its type should go in the Script Editor. To open the script editor type: <Alt>+R. Alternatively, you can go to the Tools Menu -> Script editor. | + | All your code, regardless of its type, should go in the Script Editor. To open the script editor type: <Alt>+R. Alternatively, you can go to the Tools Menu -> Script editor. |

| − | All Events go in the "Remote" tab of the script editor. Popups go in the "Popups" tab of the script editor. Aliases are special | + | All Events go in the "Remote" tab of the script editor. Popups go in the "Popups" tab of the script editor. Aliases are special, in that they may go in the "Remote" tab, if and only if the code is prefixed with the "alias" keyword, or they can go in the "Aliases" tab, which does not require the "alias" prefix.. |

[[File:Remote menu.png|center|Remote Editor]] | [[File:Remote menu.png|center|Remote Editor]] | ||

== The very basics == | == The very basics == | ||

| − | Before we can do anything productive, we must understand some of the most basic parts of a script. | + | Before we can do anything productive, we must understand some of the most basic parts of a script. Therefore, let's take a few moments to help familiarize you with the following key components: |

=== Statements === | === Statements === | ||

| − | Every script is composed of one or more statements. Each statement must go on its own line or separated by a pipe. For example, the following two are the same: | + | Every script is composed of one or more statements. A statement describes something that needs to happen. Each statement must go on its own line, or it must be separated by a pipe, which is the '|' symbol. For example, the following two are the same: |

| + | ===== Piping ===== | ||

<pre>statement 1 | statement 2 | statement 3 | statement 4</pre> | <pre>statement 1 | statement 2 | statement 3 | statement 4</pre> | ||

and: | and: | ||

| + | ===== Code blocks ===== | ||

<pre>statement 1 | <pre>statement 1 | ||

statement 2 | statement 2 | ||

| Line 26: | Line 28: | ||

=== What's with the slashes? === | === What's with the slashes? === | ||

| − | If you asked any script related question in a help channel, you were probably told to type some code that begin with a forward slash. In order to execute any code from the mIRC editbox (the | + | If you asked any script related question in a help channel, you were probably told to type some code that begin with a forward slash. In order to execute any code from the mIRC editbox (the box where you normally type all of your text), you must prefix the code with two forward slashes; in some cases, you will only need to use a single slash, which we will talk about later. |

=== /echo command === | === /echo command === | ||

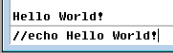

| − | + | The most common type of statements are [[commands - mIRC|commands]]. Commands are a way to tell mIRC to perform a basic operation. By far the most common command you will be using is the [[/echo command - mIRC|/echo command]]. The /echo command simply prints text to the screen. Every echo command prints on a line of its own. | |

| − | Let's | + | Let's dive right into an example! Type the following code into your editbox: |

<source lang="mIRC">//echo Hello World!</source> | <source lang="mIRC">//echo Hello World!</source> | ||

| − | You should see the following result: | + | When you are finished typing this echo command, hit your Return or Enter key on your keyboard. You should see the following result ('''Note:''' Your editbox will not have anything in it, it will be clear once you press the Enter or Return key): |

<pre>Hello World!</pre> | <pre>Hello World!</pre> | ||

[[File:Hello edit.png]] | [[File:Hello edit.png]] | ||

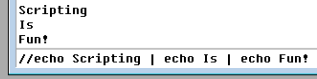

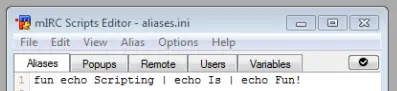

| − | Recall we said earlier that multiple statements can be combined by using the pipe | + | Recall we said earlier that multiple statements can be combined by using the pipe '|'? Let's print 3 lines to the screen using the echo command and some pipes. Type the following code into your editbox (''Remember to hit the Return or Enter keys from now on''): |

<source lang="mIRC">//echo Scripting | echo Is | echo Fun!</source> | <source lang="mIRC">//echo Scripting | echo Is | echo Fun!</source> | ||

| Line 50: | Line 52: | ||

Fun!</pre> | Fun!</pre> | ||

[[File:Fun edit.png]] | [[File:Fun edit.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | You will notice that after the first ''//echo'' command, once we've piped, we do not need to type anymore slashes; this is because mIRC interprets the rest of the statements via the first initial slash(es). | ||

=== Let's make it into an alias, shall we? === | === Let's make it into an alias, shall we? === | ||

| − | + | When we talked about aliases in the beginning of this tutorial, we said they are used to describe any piece of scripting code that can be reused. Aliases have a name by which we can refer to them, and they also have a body. The body of an alias contains a statement, or a list of statements, that execute(s) when we call that alias. You can think of aliases as commands, much like the ''echo'' command is. All aliases can be called from your edit box by preceding them with one ore two forward-slashes. | |

| + | |||

| + | ==== Basic Alias ==== | ||

| + | A basic alias will look something like this: | ||

<pre>alias name <statement></pre> | <pre>alias name <statement></pre> | ||

| − | We can tweak | + | We can tweak the statement of this alias just a little in order to perform multiple statements through the use of piping: |

<pre>alias name statement 1 | statement 2 | statement 3</pre> | <pre>alias name statement 1 | statement 2 | statement 3</pre> | ||

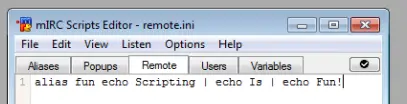

| − | Let's make the code we used above to print "Scripting Is Fun!" | + | Notice that with the piping, this alias now performs multiple actions. |

| + | |||

| + | Let's make the code we used above to print "Scripting Is Fun!", all on separate lines, and call this new alias "fun": | ||

<source lang="mIRC">alias fun echo Scripting | echo Is | echo Fun!</source> | <source lang="mIRC">alias fun echo Scripting | echo Is | echo Fun!</source> | ||

| − | + | Before we continue, let us note a few things regarding the above code: | |

| + | |||

| + | # The two // where removed; we only really need one or two forward-slashes when we want to execute code directly from the editbox. Using slashes in your script editor adds nothing but clutter. | ||

| + | # Because we used the '''alias''' keyword, the code must go in the '''Remote Tab''' of the script editor. In order to use that code from the aliases tab, you must remove the "alias" keyword. The rest of the code stays the same. | ||

=== Remote tab === | === Remote tab === | ||

| Line 71: | Line 83: | ||

[[File:Fun alias 2.png]] | [[File:Fun alias 2.png]] | ||

| − | '''Note:''' When you want to execute an alias you would | + | '''Note:''' When you want to execute an alias, you would refer to it as wanting to ''call the alias''. |

| − | To call our alias | + | To call on our alias ''fun'', all we have to do is use its name, preceded by a forward-slash in any mIRC editbox: |

<pre>/fun</pre> | <pre>/fun</pre> | ||

| + | '''Note:''' Two forward-slashes will also call it, but for now, let's only use a single forward-slash | ||

That should print our text again: | That should print our text again: | ||

| Line 84: | Line 97: | ||

== A block of code: == | == A block of code: == | ||

| − | When we have a group of related commands, we call it a '''block of code'''. Most scripts, however, are not as short as our example and putting it all on one long line is messy. We can use the second format we talked about which is storing each statement on a new line | + | When we have a group of related commands, we call it a '''block of code'''. Most scripts, however, are not as short as our example and putting it all on one long line, or ''piping'', is messy. We can use the second format we talked about, which is storing each statement on a new line, in order to keep our code clean and easily editable. The way that we accomplish the task of creating a code block is to tell mIRC "this block of code belongs to this alias". We do that by enclosing the block of code in a pair of brackets: |

<source lang="mIRC">alias name { | <source lang="mIRC">alias name { | ||

| Line 94: | Line 107: | ||

A few notes about the language limitations: | A few notes about the language limitations: | ||

| − | # The opening bracket ( | + | # <span style="color: #DB0000;">The opening bracket ('''{''') '''must''' be on the same line as the alias keyword</span> |

| − | # The opening bracket '''must not''' touch anything | + | # <span style="color: #DB0000;">The opening bracket '''must not''' touch anything</span> |

| − | # The closing bracket '''must not''' touch anything else | + | # <span style="color: #DB0000;">The closing bracket '''must not''' touch anything else</span> |

| − | # The closing bracket '''must''' be the last part of the block of code. | + | # <span style="color: #DB0000;">The closing bracket '''must''' be the last part of the block of code</span> |

| + | |||

| + | === <span style="color: #256B22;">Right Examples</span> === | ||

| + | |||

| + | <pre>alias example { echo hello! }</pre> | ||

| + | Note the spaces before and after both the opening and closing brackets. This is a good example of a proper code block. | ||

| − | === Wrong | + | |

| + | <pre>alias example { | ||

| + | echo hello! | ||

| + | }</pre> | ||

| + | The initial opening bracket is on the same line as the alias name, and it has proper spacing before itself. The statement | ||

| + | within the block is also perfectly executed, and the closing bracket is on its own line. This is another example of a proper | ||

| + | code block. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === <span style="color: #9E1010;">Wrong Examples</span> === | ||

<pre>alias example{echo hello! }</pre> | <pre>alias example{echo hello! }</pre> | ||

| + | The opening bracket is touching the "example" and "echo". | ||

| − | |||

<pre>alias example { echo hello!}</pre> | <pre>alias example { echo hello!}</pre> | ||

| + | The closing bracket is touching the "hello!". | ||

| − | |||

<pre>alias example | <pre>alias example | ||

| Line 113: | Line 140: | ||

echo hello! | echo hello! | ||

}</pre> | }</pre> | ||

| + | The opening bracket must be on the same line as the "alias" keyword. | ||

| − | |||

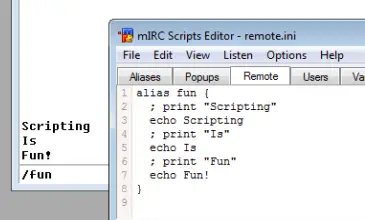

=== Using a block of code === | === Using a block of code === | ||

| − | Let's | + | Let's reuse the ''fun'' alias from before. However, this time we will put each statement on its own line: |

<source lang="mIRC">alias fun { | <source lang="mIRC">alias fun { | ||

| Line 124: | Line 151: | ||

echo Fun! | echo Fun! | ||

}</source> | }</source> | ||

| + | Notice how this is a perfect example of a Good code block, much like the sample that we viewed above? If | ||

| + | you are noticing the repetitiveness of the ''echo'' command, don't worry, in later examples we will show | ||

| + | you tricks on how to get around repeating certain reused commands in your code. | ||

| + | |||

== Comments == | == Comments == | ||

| − | Comments are normal, readable | + | Comments are normal, readable text that can be placed inside of your script, and they are a good practice to help better explain to other scripters what's going on in your code. Technically speaking, a comment can say whatever you want it to say, and they are ignored when the program is executed, meaning they have no effect on the actual behavior of the code. |

| + | |||

| + | All comments are preceded by the ''';''' character, which is the semi-colon. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Single-line Comments === | ||

| + | The most basic comment is the '''single-line comment''', which has the following syntax: | ||

<source lang="mIRC">; This is single-line comment.</source> | <source lang="mIRC">; This is single-line comment.</source> | ||

| − | + | Note on how the comment begins with a semicolon and ends at the end of the line; anything on this line is now ignored. | |

| + | |||

| + | Here is another basic example of a single-line comment: | ||

<source lang="mIRC">alias fun { | <source lang="mIRC">alias fun { | ||

; print "Scripting" | ; print "Scripting" | ||

| Line 142: | Line 180: | ||

[[File:Fun comment.png]] | [[File:Fun comment.png]] | ||

| − | The second type of comment is the multi-line comment. A multi-line comment can, as its name suggests, span multiple lines. The syntax for a multi-line comment is: | + | === Multi-line Comments === |

| + | The second type of comment is the multi-line comment. A multi-line comment can, as its name suggests, span multiple lines. Multi-line comments are enclosed between the '''/*''' & '''*/''' characters. The syntax for a multi-line comment is: | ||

<source lang="mIRC">/* This is | <source lang="mIRC">/* This is | ||

| Line 148: | Line 187: | ||

comment! | comment! | ||

*/</source> | */</source> | ||

| − | Your text must go between the /* and the */. | + | Your text must go between the /* and the */ in order for it to be treated as a comment. |

A few notes about the language limitations: | A few notes about the language limitations: | ||

| − | + | # Text may touch the opening '''/*''' | |

| − | + | # The closing '''*/''' must be on a line of its own | |

| + | |||

| + | === <span style="color: #256B22;">Right Examples</span> === | ||

| + | <pre>/* testing | ||

| + | out | ||

| + | a multi-line | ||

| + | comment | ||

| + | */</pre> | ||

| + | or | ||

| + | <pre>/* | ||

| + | testing | ||

| + | out | ||

| + | a multi-line | ||

| + | comment | ||

| + | */</pre> | ||

| + | In both of the above examples, the opening comment parameters are properly executed, | ||

| + | the lines are spaced out and the closing parameters are by themselves. These are both | ||

| + | examples of proper multi-line comment blocks. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | === <span style="color: #9E1010;">Wrong Examples</span> === | ||

| + | <pre>/* testing | ||

| + | test */</pre> | ||

The */ is not on a line of Its own. | The */ is not on a line of Its own. | ||

| + | |||

/* comment */ | /* comment */ | ||

The */ is not on a line of Its own. | The */ is not on a line of Its own. | ||

| + | |||

== Identifiers == | == Identifiers == | ||

{{main|aliases - mIRC}} | {{main|aliases - mIRC}} | ||

| − | Before we wrap up this tutorial we need to talk about one last concept: $identifiers. All identifiers have a dollar symbol sigil and have the following syntax | + | Before we wrap up this tutorial, we need to talk about one last concept: $identifiers. All identifiers have a dollar symbol sigil and have the following syntax: |

<source lang="mIRC">$name | <source lang="mIRC">$name | ||

| Line 171: | Line 229: | ||

$name(<argument 1>, <argument 2>, <argument 3>, ...)</source> | $name(<argument 1>, <argument 2>, <argument 3>, ...)</source> | ||

| − | Identifiers are very similar to commands except that we use identifiers when we want some value. For example, if we want to print out | + | Identifiers are very similar to commands except that we use identifiers when we want some value. For example, if we want to print out your current nickname, we would use the following code: |

<source lang="mIRC">//echo -a $me</source> | <source lang="mIRC">//echo -a $me</source> | ||

| Line 180: | Line 238: | ||

<source lang="mIRC">$rand(<low>, <high>)</source> | <source lang="mIRC">$rand(<low>, <high>)</source> | ||

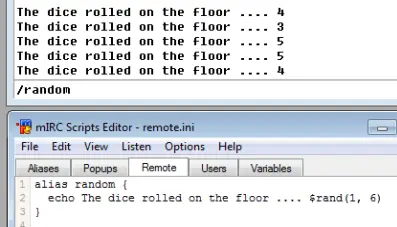

| − | Given | + | Given both low bound and high bound number values, $rand will return a random number in between, and including, the two numbers. For example: |

<source lang="mIRC">alias random { | <source lang="mIRC">alias random { | ||

| Line 189: | Line 247: | ||

[[File:Random example.png]] | [[File:Random example.png]] | ||

| + | The results that mIRC generates for you will be different than the ones listed above in the screenshot; this is the nature of the $rand identifier. | ||

| − | == | + | == On your own: == |

| − | + | Below are a very few, basic commands that you can use to experiment with in a safe manner. Go ahead, try them out! | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Below are a few | ||

=== Colors: === | === Colors: === | ||

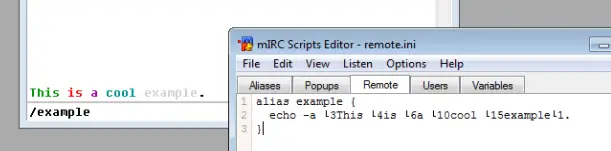

| − | Just like you can add colors when you talk by typing | + | Just like you can add colors when you talk by typing CTRL+K on your keyboard, and then selecting a color number, you can do the same in your aliases. Here is a simple example: |

<source lang="mIRC">alias example { | <source lang="mIRC">alias example { | ||

| Line 203: | Line 259: | ||

}</source> | }</source> | ||

| − | You may have | + | You may have noticed that we added a strange new thing, '''-a'''. The -a is called a '''switch'''; switches slightly alter the way a command behaves. In the case of the ''/echo'' command, the -a switch specifies that we wanted the command to echo to the current active window. There is another switch, the '''-s switch''', which can be used to tell the echo command to print to the status window instead, regardless of which window you have open. |

| + | |||

| + | Below is an example of how we use the '''-a''' switch: | ||

[[File:Color example.png]] | [[File:Color example.png]] | ||

| Line 226: | Line 284: | ||

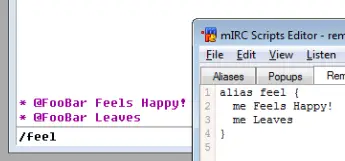

=== Actions === | === Actions === | ||

| − | Actions are very similar to your normal channel messages except they are displayed in a slightly different manner. | + | Actions are very similar to your normal channel messages, except that they are displayed in a slightly different manner. |

<source lang="mIRC">; This is good for the channel you are in right now: | <source lang="mIRC">; This is good for the channel you are in right now: | ||

| Line 240: | Line 298: | ||

}</source> | }</source> | ||

| − | The code should produce something like this | + | The code should produce something like this (''Your name will obviously be different''): |

<span style="color: #9C009C;">* @FooBar Feels Happy! | <span style="color: #9C009C;">* @FooBar Feels Happy! | ||

| Line 253: | Line 311: | ||

describe #MyChannel Leaves | describe #MyChannel Leaves | ||

}</source> | }</source> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Where do we go from here? == | ||

| + | By now you should be grasping the basics of mSL, or at the very least beginning to understand how things work. It is highly recommended that you take it upon yourself to play around with the code on your own, in order to see what happens when you change different things around. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Next up is are the [[alias - mIRC|aliases]]. If you feel comfortable with aliases, feel free to move on to [[variables - mIRC|variables]]. | ||

[[Category:mIRC]] | [[Category:mIRC]] | ||

Revision as of 20:27, 22 December 2013

This article focuses on the very basics of mIRC. The target audience is people with no knowledge, or very limited knowledge, of the mIRC scripting language.

Contents

Where does the code go?

All your code, regardless of its type, should go in the Script Editor. To open the script editor type: <Alt>+R. Alternatively, you can go to the Tools Menu -> Script editor.

All Events go in the "Remote" tab of the script editor. Popups go in the "Popups" tab of the script editor. Aliases are special, in that they may go in the "Remote" tab, if and only if the code is prefixed with the "alias" keyword, or they can go in the "Aliases" tab, which does not require the "alias" prefix..

The very basics

Before we can do anything productive, we must understand some of the most basic parts of a script. Therefore, let's take a few moments to help familiarize you with the following key components:

Statements

Every script is composed of one or more statements. A statement describes something that needs to happen. Each statement must go on its own line, or it must be separated by a pipe, which is the '|' symbol. For example, the following two are the same:

Piping

statement 1 | statement 2 | statement 3 | statement 4

and:

Code blocks

statement 1 statement 2 statement 3 statement 4

What's with the slashes?

If you asked any script related question in a help channel, you were probably told to type some code that begin with a forward slash. In order to execute any code from the mIRC editbox (the box where you normally type all of your text), you must prefix the code with two forward slashes; in some cases, you will only need to use a single slash, which we will talk about later.

/echo command

The most common type of statements are commands. Commands are a way to tell mIRC to perform a basic operation. By far the most common command you will be using is the /echo command. The /echo command simply prints text to the screen. Every echo command prints on a line of its own.

Let's dive right into an example! Type the following code into your editbox:

//echo Hello World!

When you are finished typing this echo command, hit your Return or Enter key on your keyboard. You should see the following result (Note: Your editbox will not have anything in it, it will be clear once you press the Enter or Return key):

Hello World!

Recall we said earlier that multiple statements can be combined by using the pipe '|'? Let's print 3 lines to the screen using the echo command and some pipes. Type the following code into your editbox (Remember to hit the Return or Enter keys from now on):

//echo Scripting | echo Is | echo Fun!

You should hopefully see the following results:

Scripting Is Fun!

You will notice that after the first //echo command, once we've piped, we do not need to type anymore slashes; this is because mIRC interprets the rest of the statements via the first initial slash(es).

Let's make it into an alias, shall we?

When we talked about aliases in the beginning of this tutorial, we said they are used to describe any piece of scripting code that can be reused. Aliases have a name by which we can refer to them, and they also have a body. The body of an alias contains a statement, or a list of statements, that execute(s) when we call that alias. You can think of aliases as commands, much like the echo command is. All aliases can be called from your edit box by preceding them with one ore two forward-slashes.

Basic Alias

A basic alias will look something like this:

alias name <statement>

We can tweak the statement of this alias just a little in order to perform multiple statements through the use of piping:

alias name statement 1 | statement 2 | statement 3

Notice that with the piping, this alias now performs multiple actions.

Let's make the code we used above to print "Scripting Is Fun!", all on separate lines, and call this new alias "fun":

alias fun echo Scripting | echo Is | echo Fun!

Before we continue, let us note a few things regarding the above code:

- The two // where removed; we only really need one or two forward-slashes when we want to execute code directly from the editbox. Using slashes in your script editor adds nothing but clutter.

- Because we used the alias keyword, the code must go in the Remote Tab of the script editor. In order to use that code from the aliases tab, you must remove the "alias" keyword. The rest of the code stays the same.

Remote tab

Aliases tab

Note: When you want to execute an alias, you would refer to it as wanting to call the alias.

To call on our alias fun, all we have to do is use its name, preceded by a forward-slash in any mIRC editbox:

/fun

Note: Two forward-slashes will also call it, but for now, let's only use a single forward-slash

That should print our text again:

Scripting Is Fun!

A block of code:

When we have a group of related commands, we call it a block of code. Most scripts, however, are not as short as our example and putting it all on one long line, or piping, is messy. We can use the second format we talked about, which is storing each statement on a new line, in order to keep our code clean and easily editable. The way that we accomplish the task of creating a code block is to tell mIRC "this block of code belongs to this alias". We do that by enclosing the block of code in a pair of brackets:

alias name { statement 1 statement 2 statement 3 }

A few notes about the language limitations:

- The opening bracket ({) must be on the same line as the alias keyword

- The opening bracket must not touch anything

- The closing bracket must not touch anything else

- The closing bracket must be the last part of the block of code

Right Examples

alias example { echo hello! }

Note the spaces before and after both the opening and closing brackets. This is a good example of a proper code block.

alias example {

echo hello!

}

The initial opening bracket is on the same line as the alias name, and it has proper spacing before itself. The statement within the block is also perfectly executed, and the closing bracket is on its own line. This is another example of a proper code block.

Wrong Examples

alias example{echo hello! }

The opening bracket is touching the "example" and "echo".

alias example { echo hello!}

The closing bracket is touching the "hello!".

alias example

{

echo hello!

}

The opening bracket must be on the same line as the "alias" keyword.

Using a block of code

Let's reuse the fun alias from before. However, this time we will put each statement on its own line:

alias fun { echo Scripting echo Is echo Fun! }

Notice how this is a perfect example of a Good code block, much like the sample that we viewed above? If you are noticing the repetitiveness of the echo command, don't worry, in later examples we will show you tricks on how to get around repeating certain reused commands in your code.

Comments

Comments are normal, readable text that can be placed inside of your script, and they are a good practice to help better explain to other scripters what's going on in your code. Technically speaking, a comment can say whatever you want it to say, and they are ignored when the program is executed, meaning they have no effect on the actual behavior of the code.

All comments are preceded by the ; character, which is the semi-colon.

Single-line Comments

The most basic comment is the single-line comment, which has the following syntax:

; This is single-line comment.

Note on how the comment begins with a semicolon and ends at the end of the line; anything on this line is now ignored.

Here is another basic example of a single-line comment:

alias fun { ; print "Scripting" echo Scripting ; print "Is" echo Is ; print "Fun" echo Fun! }

Multi-line Comments

The second type of comment is the multi-line comment. A multi-line comment can, as its name suggests, span multiple lines. Multi-line comments are enclosed between the /* & */ characters. The syntax for a multi-line comment is:

/* This is a multi-line comment! */

Your text must go between the /* and the */ in order for it to be treated as a comment.

A few notes about the language limitations:

- Text may touch the opening /*

- The closing */ must be on a line of its own

Right Examples

/* testing out a multi-line comment */

or

/* testing out a multi-line comment */

In both of the above examples, the opening comment parameters are properly executed, the lines are spaced out and the closing parameters are by themselves. These are both examples of proper multi-line comment blocks.

Wrong Examples

/* testing test */

The */ is not on a line of Its own.

/* comment */

The */ is not on a line of Its own.

Identifiers

- Main article: aliases - mIRC

Before we wrap up this tutorial, we need to talk about one last concept: $identifiers. All identifiers have a dollar symbol sigil and have the following syntax:

$name ;or $name(<argument 1>, <argument 2>, <argument 3>, ...)

Identifiers are very similar to commands except that we use identifiers when we want some value. For example, if we want to print out your current nickname, we would use the following code:

//echo -a $me

$rand()

One of the most common operations we use is to generate random numbers. This is where the $rand() identifier comes into play; it can generate a random number between a given range. The $rand() has the following syntax:

$rand(<low>, <high>)

Given both low bound and high bound number values, $rand will return a random number in between, and including, the two numbers. For example:

alias random { echo The dice rolled on the floor .... $rand(1, 6) }

Here is what we got when we called out /random alias a few times:

The results that mIRC generates for you will be different than the ones listed above in the screenshot; this is the nature of the $rand identifier.

The results that mIRC generates for you will be different than the ones listed above in the screenshot; this is the nature of the $rand identifier.

On your own:

Below are a very few, basic commands that you can use to experiment with in a safe manner. Go ahead, try them out!

Colors:

Just like you can add colors when you talk by typing CTRL+K on your keyboard, and then selecting a color number, you can do the same in your aliases. Here is a simple example:

alias example { echo -a �3This �4is �6a �10cool �15example�1. }

You may have noticed that we added a strange new thing, -a. The -a is called a switch; switches slightly alter the way a command behaves. In the case of the /echo command, the -a switch specifies that we wanted the command to echo to the current active window. There is another switch, the -s switch, which can be used to tell the echo command to print to the status window instead, regardless of which window you have open.

Below is an example of how we use the -a switch:

Will produce:

This is a cool example.

//echo -a The number �42� is even.

Will produce the following result:

The number is even.

Notice that the number is not showing. That's because it was considered part of the color number '42'. Prefixing the color value with a zero will fix this issue:

//echo -a The number �042� is even.

Will produce the following result:

The number 2 is even.

Actions

Actions are very similar to your normal channel messages, except that they are displayed in a slightly different manner.

; This is good for the channel you are in right now: me <message> ; This is good for any channel you specify (as long as you are in that channel) describe <#channe> <message>

For example:

alias feel { me Feels Happy! me Leaves }

The code should produce something like this (Your name will obviously be different):

* @FooBar Feels Happy!

* @FooBar Leaves

If we wanted to specify a channel, we could have used:

alias feel { describe #MyChannel Feels Happy! describe #MyChannel Leaves }

Where do we go from here?

By now you should be grasping the basics of mSL, or at the very least beginning to understand how things work. It is highly recommended that you take it upon yourself to play around with the code on your own, in order to see what happens when you change different things around.

Next up is are the aliases. If you feel comfortable with aliases, feel free to move on to variables.